Why I Write “Palestinian” in Quotation Marks — And Why the Evidence Supports This Choice

What newspapers, scholars, Arab leaders, and historical documents actually said — and why it matters today

Language and Warfare (Foundations): Part of an ongoing series on how weaponized terminology shapes our understanding of Jews, Israel, and their enemies.

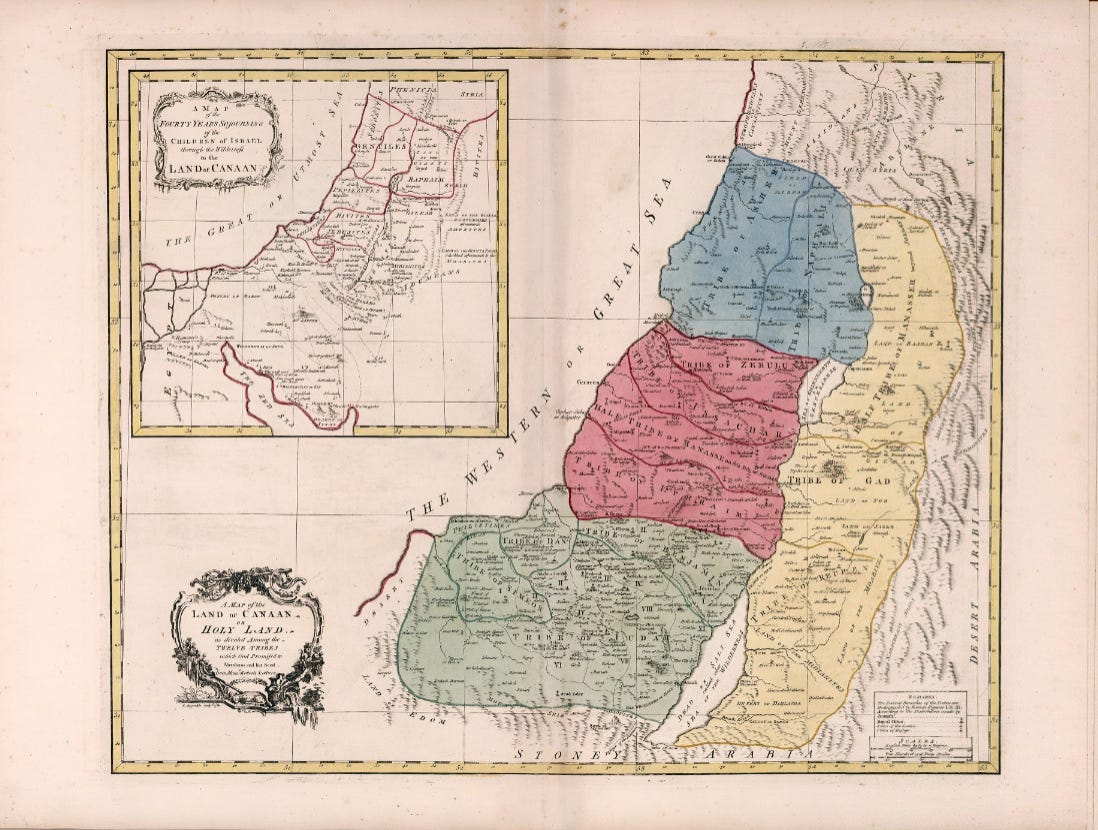

To ground the reader in the deep historical context, this eighteenth-century map depicts the traditional divisions of the Land of Israel—Judea, Samaria, and the surrounding tribal regions—centuries before modern political terminology emerged.

Figure 1. A Map of the Land of Canaan or Holy Land as Divided Among the Twelve Tribes (Roberts; engraved by J. Gibson; published in Jean Palairet’s* Atlas Méthodique,* London and The Hague, 1755). Courtesy of the David Rumsey Historical Map Collection.

Access the original map here:

https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/detail/RUMSEY~8~1~290896~90068360

Preface

This essay examines the historical development of the modern “Palestinian” identity category as a scholarly question—not as a political polemic. I am not denying the existence or humanity of the Arab population living in Gaza, nor in Judea and Samaria. Rather, I am situating the term “Palestinian” within its proper historical, political, and methodological context.

The quotation marks I use are not derogatory; they are methodological. They denote a contested identity category whose modern form emerged only in the twentieth century and whose historical antecedents are absent from antiquity, medieval sources, and Ottoman administrative documents. These marks signal analytical distance and historical precision. They do not diminish human worth.

This essay draws on Arab, Jewish, and international scholars; primary-source admissions by leaders of the “Palestinian” movement; testimony from insiders such as Mosab Hassan Yousef; and the global academic literature on nationalism. It culminates in a scholarly—not political—recommendation: that we employ quotation marks around “Palestinian” when referring to identity claims that did not exist prior to the twentieth century, so as to preserve terminological integrity and resist retroactive mythmaking.

I. What the Historical Record Does Not Show

There is no evidence of an ancient or medieval “Palestinian” people. Regional identities prior to the twentieth century were rooted in clan (hamula), town or city (e.g., Jaffawi, Khalili, Nabulsi), religious affiliation, and broader Arab or Syrian self-conceptions.

Arab historians such as Philip Hitti and George Antonius—foundational figures in Arab historiography and nationalism—explicitly described the region as part of Greater Syria, not as the homeland of a distinct “Palestinian” nation. Their work is unambiguous on this point.

II. The Mandate Period: Localism, Not Nationhood

Scholars such as Yehoshua Porath, Eliezer Tauber, and Mordechai Kedar have demonstrated that during the British Mandate period, political mobilization in the territory was not centered on a common national identity. Rather:

clan rivalries (especially Husayni vs. Nashashibi) dominated political life

loyalties were regional or urban

pan-Arab and “Southern Syria” frameworks overshadowed parochial ones

no unified “Palestinian” national consciousness emerged

As Porath showed, early political organizations defined themselves overwhelmingly as Arab or Syrian—not “Palestinian.”

III. The Term “Palestinian” Before 1948: Who Did It Refer To?

Before 1948, the term “Palestinian” overwhelmingly referred to Jews or to the land, not to a distinct Arab people.

Prominent examples include:

the Palestine Symphony Orchestra – a Jewish orchestra founded by Bronisław Huberman

Palestine Airways – a Jewish-owned airline

the Palestine Post – a Jewish newspaper (later The Jerusalem Post)

British Mandate passports labeled residents as “Palestine Jews,” “Palestine Christians,” and occasionally “Palestine Arabs,” but did not recognize a “Palestinian” nationality

Figure 2. Headline from the New York Times, December 4, 1945: “Arabs to Boycott Palestinian Goods.” At the time, the term “Palestinian goods” referred to Jewish-manufactured products from Mandatory Palestine. This headline, like countless others, demonstrates that the modern ethnonational usage of “Palestinian” is a post-1948 political development.

In this period, newspapers, governments, and international bodies consistently used “Palestinian” to signify Jews or Jewish institutions, and “Arabs” to signify the region’s Arab population. The distinction was clear and widely understood.

IV. 1948 and After: Territory vs. People

Following the Arab invasion of the new State of Israel in 1948, two key developments reshaped the region:

Jordan annexed Judea and Samaria, granting local Arabs Jordanian citizenship and referring to the territory as the “West Bank”—a term invented only after 1948 to obscure Jewish historical claims.

Egypt placed Gaza under military rule, without creating or recognizing a separate “Palestinian” nationality.

No Arab state claimed that a distinct “Palestinian” people existed.

Figure 3. Front page of the New York Times, May 16, 1948: “Arab Armies Invade Palestine; Reach Gaza, Bomb Tel Aviv Again.” This headline uses “Palestine” as a territorial term and “Arab armies” to describe the invading forces. Nowhere does the paper refer to “Palestinian armies” or a “Palestinian people.”

This clear separation between land (“Palestine”) and people (“Arabs”) was standard across global media.

V. Another Example of Territorial, Not National, Usage

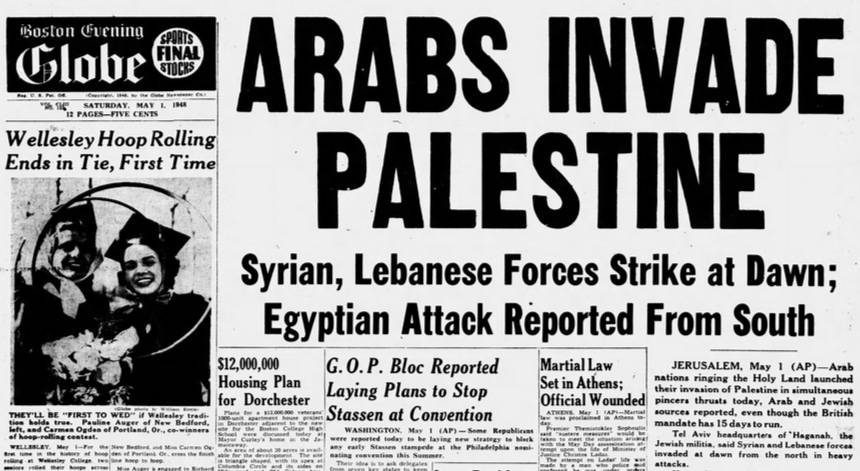

Figure 4. Front page of the Boston Globe, May 1, 1948: “Arabs Invade Palestine.” Like the New York Times headline, this one distinguishes between “Arabs” as a people and “Palestine” as a geographic area. The term did not denote an Arab nationality at the time.

Together, these headlines form a consistent evidentiary record across the English-speaking world, reinforcing that “Palestine” was a place—not a nation.

VI. Judea and Samaria: Historical Realities vs. Political Inventions

The terms Judea and Samaria are historically attested for millennia, appearing in biblical texts, classical histories, medieval chronicles, and Western cartography without interruption. These names reflect the region’s continuous Jewish presence and its deep historical roots.

The term “West Bank,” by contrast, was created in 1950 by the Hashemite regime after its illegal occupation of the western bank of the Jordan River—an annexation recognized by almost no state. Using Judea and Samaria is historically accurate. Using “West Bank” uncritically is to adopt a mid-twentieth-century political euphemism designed to obscure historical continuity with Jewish antiquity.

A similar problem arises with the modern phrase “Occupied Palestinian Territories” (OPT). Despite its ubiquity in journalism, diplomacy, and much of academia, it has no historical antecedent in any British Mandate document, Ottoman administrative register, Arab political memorandum, or United Nations text from 1947–48. The region currently labeled as the “OPT” was never described as “Palestinian” territory prior to 1967, nor was it under a recognized Palestinian state. It was Judea and Samaria—later seized and annexed by Jordan, whose claim was accepted by virtually no one.

To apply the term “Occupied Palestinian Territories” retroactively is therefore not an act of historical description but a projection of late-twentieth-century political terminology backward onto earlier periods. The phrase is no more historically grounded than “West Bank,” and both obscure more than they clarify. Precise terminology matters because it anchors the reader to what the region was actually called by the people and institutions of the time, rather than by political narratives formed decades later.

This same pattern of retroactive labeling appears not only in territorial descriptions, but also in the modern ethnonational use of the term “Palestinian,” which entered political vocabulary long after the periods in question.

VII. Arab and “Palestinian” Voices Acknowledging Construction

Multiple Arab and “Palestinian” figures have openly acknowledged that modern “Palestinian” identity is a constructed response to twentieth-century political developments rather than an ancient ethnonational reality. These admissions, made across decades and ideological camps, reinforce the documentary record.

Zuhair Mohsen, a senior PLO official, stated bluntly in a 1977 interview that a distinct Palestinian people existed chiefly for “political and tactical reasons,” adding that broader Arab unity remained the movement’s ultimate aim. Salah Khalaf (Abu Iyad), one of the PLO’s founders, wrote that modern Palestinian identity crystallized only after 1948—and especially after the 1967 war—as a reaction to shifting regional power dynamics. Hanan Ashrawi, a leading “Palestinian” intellectual, has similarly acknowledged that the idea of Palestinian peoplehood grew primarily in response to British policy and the rise of Zionism.

Even insider critics such as Mosab Hassan Yousef describe how internal elites, especially Hamas leadership, deliberately shaped “Palestinian” identity by mobilizing narratives that often contradicted historical fact. According to Yousef, identity was molded through indoctrination, mythmaking, and political necessity—not deep-rooted nationhood.

Taken together, these testimonies reflect a broader pattern: the identities invoked in the Arab–Israeli conflict are often shaped by political circumstances rather than inherited from distant antiquity. This is not unique to “Palestinian” identity; it is characteristic of modern Arab political consciousness more generally.

As Albert Hourani demonstrated in Arabic Thought in the Liberal Age, modern Arab nationalism emerged not from an ancient, continuous ethnonational consciousness but from the intellectual and political ferment of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Hourani emphasized that Arab identity during this period was shaped by new political ideas, elite debates, colonial pressures, and regional crises—not by primordial national traditions. He showed that local identities in the Levant—whether tied to village, clan, city, or a broader Syrian affiliation—remained primary well into the Mandate period. If Arab nationalism itself was a modern construct, then its later regional variations—including the modern “Palestinian” national identity—necessarily arose even later and as part of the same historical process. Hourani’s analysis reinforces the point that the emergence of a distinct “Palestinian” ethnonational identity is a recent political development rather than a deeply rooted historical continuum.

This broader scholarly understanding of nationalism provides the necessary framework for interpreting how modern political identities—especially in the Middle East—are formed, articulated, and projected backward into history. It is these theoretical foundations that help explain why the modern usage of “Palestinian” diverges so sharply from the terminology of earlier eras.

VIII. Nationalism Theory and the Modern “Palestinian” Identity

The leading theorists of nationalism—Benedict Anderson, Ernest Gellner, Eric Hobsbawm, Walker Connor, Anthony D. Smith—agree that:

nations are modern constructs

they are not ancient or timeless

they result from political mobilization, selective memory, media narratives, and shared myths

The modern “Palestinian” identity fits this model precisely: its emergence is late, political, and reactive.

IX. Why I Use Quotation Marks Around “Palestinian”

The quotation marks serve several scholarly purposes:

they mark the term as contested and modern

they avoid projecting a recent political identity backward into periods where it did not exist

they uphold historical accuracy

they prevent ideological narratives from overwriting documentary evidence

Again, this is not a denial of any person’s humanity. It is simply a refusal to endorse historical inaccuracies.

X. A Scholar’s Recommendation

Writers, analysts, and scholars should employ quotation marks around “Palestinian” when discussing periods prior to the twentieth century, or when referencing modern identity constructs whose historical foundations are recent and politically motivated.

This is not a political prescription; it is a call for historical clarity.

I. Primary Archival Newspapers & Periodicals

Boston Evening Globe. “Arabs Invade Palestine.” May 1, 1948.

New York Times. “Arabs to Boycott Palestinian Goods.” December 4, 1945.

New York Times. “Arab Armies Invade Palestine; Reach Gaza, Bomb Tel Aviv Again; U.S. Considers Lifting Arms Ban.” May 16, 1948.

Palestine Post. Various issues, 1930s–1948. (Now The Jerusalem Post.)

II. British Mandate & Official Documents

British Government. Report by His Majesty’s Government to the Council of the League of Nations on the Administration of Palestine and Transjordan. London: HMSO, various years.

Palestine Exploration Fund. Survey of Western Palestine. London: PEF, 1870s–1880s.

League of Nations. Mandate for Palestine. London, 1922.

Israel State Archives. Mandate-era passport files, administrative correspondence, and immigration documents.

III. Arab Leaders, Intellectuals & Memoirs

Abu Iyad (Salah Khalaf), with Eric Rouleau. My Home, My Land: A Narrative of the Palestinian Struggle. New York: Times Books, 1981.

Antonius, George. The Arab Awakening: The Story of the Arab National Movement. London: Hamish Hamilton, 1938.

Ashrawi, Hanan. This Side of Peace: A Personal Account. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995.

Hitti, Philip K. History of Syria: Including Lebanon and Palestine. London: Macmillan, 1951.

Mohsen, Zuhair. Interview with Trouw (Amsterdam), March 1977.

Phares, Walid. The War of Ideas: Jihadism against Democracy. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.

Sultan, Wafa. A God Who Hates. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2009.

Yousef, Mosab Hassan, with Ron Brackin. Son of Hamas: A Gripping Account of Terror, Betrayal, Political Intrigue, and Unthinkable Choices. Carol Stream, IL: Tyndale, 2010.

IV. Israeli & Western Scholars of Middle Eastern History, Politics & Identity

Kedar, Mordechai. “Asad in Search of Legitimacy: Message and Rhetoric in the Syrian Press under Hafiz and Bashar.” In The Syrian Land, edited by Thomas Philipp and Birgit Schaebler. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner, 1998.

Kramer, Martin. Ivory Towers on Sand: The Failure of Middle Eastern Studies in America. Washington, DC: Washington Institute for Near East Policy, 2001.

Kramer, Martin. The War on Error: Israel, Islam, and the Middle East. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2010.

Lewis, Bernard. The Middle East: A Brief History of the Last 2,000 Years. New York: Scribner, 1995.

Lewis, Bernard. The Arabs in History. 6th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Porath, Yehoshua. The Emergence of the Palestinian-Arab National Movement, 1918–1929. London: Frank Cass, 1974.

Porath, Yehoshua. In Search of Arab Unity 1930–1945. London: Frank Cass, 1986.

Tauber, Eliezer. The Arab Movements in World War I. London: Routledge, 1993.

Tauber, Eliezer. The Arab–Jewish Conflict in Mandatory Palestine, 1929–1939. London: Routledge, 2021.

Karsh, Efraim. Palestine Betrayed. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010.

Karsh, Efraim. Empires of the Sand: The Struggle for Mastery in the Middle East, 1789–1923. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999.

Shapira, Anita. Israel: A History. Waltham, MA: Brandeis University Press, 2012.

V. Nationalism & Identity Formation Theory

Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso, 1983.

Connor, Walker. Ethnonationalism: The Quest for Understanding. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994.

Gellner, Ernest. Nations and Nationalism. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1983.

Hobsbawm, Eric. Nations and Nationalism since 1780: Programme, Myth, Reality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

Hourani, Albert. Arabic Thought in the Liberal Age, 1798–1939. London: Oxford University Press, 1962.

Smith, Anthony D. The Ethnic Origins of Nations. Oxford: Blackwell, 1986.

VI. Jewish Institutions in Mandatory Palestine (Cultural, Aviation, Civic)

Jewish Virtual Library. “The Palestine Philharmonic Orchestra.” Accessed 2025.

https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/the-palestine-symphony-orchestra

JFeed. “The Real History of Palestine Airways.” Accessed 2025.

https://www.jfeed.com/analysis/palestine-airways-history-truth

National Library of Israel Digital Archive. Mandate newspapers, posters, and stamps.

VII. Maps & Historical Cartography (Including Rumsey)

Roberts (mapmaker), engraved by J. Gibson. A Map of the Land of Canaan or Holy Land as Divided Among the Twelve Tribes. In Jean Palairet, Atlas Méthodique. London and The Hague: J. Nourse, P. Vaillant, and P. Gosse, 1755.

David Rumsey Historical Map Collection.

Accessed 2025:

https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/detail/RUMSEY~8~1~290896~90068360

Author Note

David E. Firester, Ph.D., is the Founder and CEO of TRAC Intelligence, LLC, and the author of Failure to Adapt: How Strategic Blindness Undermines Intelligence, Warfare, and Perception.

© 2025 David E. Firester. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted without the author’s prior written permission.

Tremendous work of academic research

Just to memorialize one item, I’m placing it here in this thread: https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1961-63v17/d34

For the sake of granting appropriate credit, it was brought to my attention by a talented person, via this post on X: https://x.com/Shoshana51728/status/2011825118817947745